translated literature

i wonder if i will find a language to speak of the things that haunt me the most

hello.

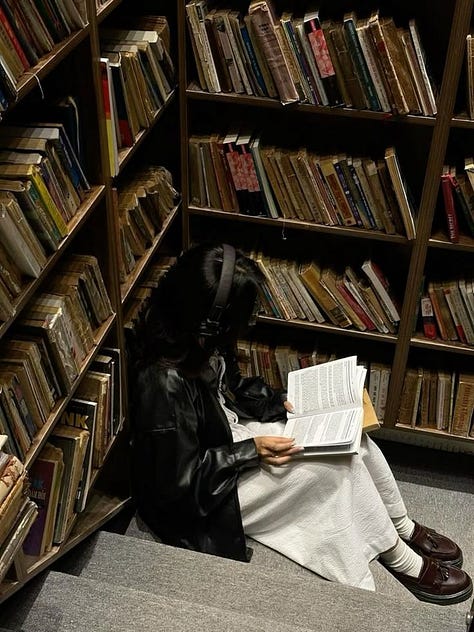

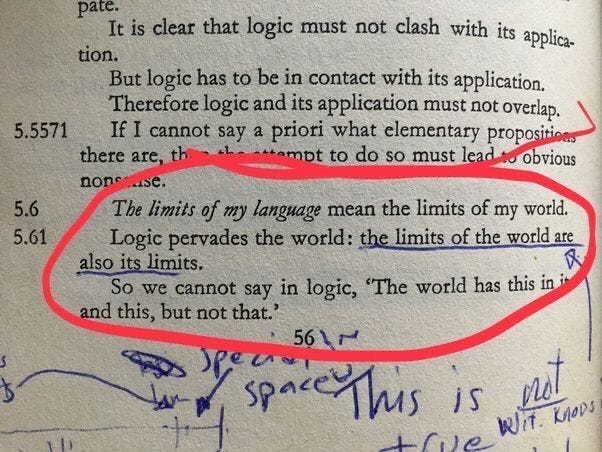

most of us only ever read in the language we were raised in. despite the fact that we live in a world where there are thousands of languages, thousands of ways to name a feeling, to hold a memory, to tell a story, for most englishspeaking readers, our literary world is mostly english. we grow up with it. we’re trained in it. we assume it’s expansive enough to contain everything we might need. but it’s not.

translated literature reminds me how limited my world has been and how much i’ve missed. it reminds me that language isn’t just about words, it’s about rhythm, silence, structure, even grammar. some languages hold entire emotional landscapes that english doesn’t. some cultures place emphasis in places that feel unfamiliar to me and sometimes a sentence arrives out of a translation feeling strange, awkward, or weighty in a way i can’t quite explain. and that can be disorienting, but it can also be beautiful. translation is not about creating perfect clarity. it’s about reaching across distance. it’s about approximation and trust. it’s about getting as close as possible to a feeling that was born in a different mouth.

i think it’s easy to assume that translated literature is inaccessible or overly intellectual, but it’s actually the opposite. it asks us to slow down. it asks us to listen. it reminds us that our way of thinking is not the default. and that kind of perspective shift is deeply important. it makes you a better reader, but it also makes you a better listener, a better observer, maybe even a better person.

i love that feeling of reading a sentence and knowing that, in its original language, it meant something slightly different. i love the tension in that. i love when a book feels like it’s been carried across time and space and somehow still found its way into my hands. and i love when a translator leaves a note in the back, explaining why they chose one word over another, how they tried to hold on to the shape of the original text while still making it sing in a new language. it reminds me that translation is an art form in itself. it’s a collaboration and a bridge.

so i’ve put together a list of some of my favorite works in translation. these are books that come from japan, korea, taiwan, brazil, austria, hungary, portugal, poland. they do not all feel the same. some are quiet, some are violent, some are strange and fragmented. but all of them have stayed with me. they each offered something i couldn’t have gotten anywhere else. and they each taught me how to read a little more slowly, a little more carefully, with a little more humility.

and right now, that bridge feels more important than ever. we live in a moment of deep cultural siloing. politically, socially, even algorithmically. it’s too easy to stay inside the narrow lane of what feels familiar. but translated literature and foreign film ask us to stretch. to listen. to step into rhythms and sensibilities that aren’t our own. they remind us how small our perspective can be and how much we miss when we only consume what was made in our own language, for our own context, with our own assumptions in mind.

there are so many other recommendations i have so maybe i will do a part two to this essay

(this post is free, but if you enjoy this newsletter, consider becoming a paid subscriber and be part of a smaller circle where things feel a little softer, a little more personal, you’ll get early access to my youtube videos and a weekly media consumption roundup filled with articles, video essays, podcasts, and other references to make you smarter. i’d love to have you there)

my favorite translated literature books

no longer human by osamu dazai

this is the book i turn to when i need to feel cracked open. it's written as a series of notebooks from a man who never really learned how to be a person. he moves through life like he’s mimicking the people around him, putting on charm like a mask, going through the motions while feeling absolutely nothing. he drinks too much, self-destructs quietly, and watches himself spiral with a kind of detachment that feels more chilling than dramatic. there’s no arc of redemption here, no moment where things turn around. the pain is quiet, constant, and completely unfixable. but somehow, reading it makes you feel less alone in your own disconnection. (japan)

kitchen by banana yoshimoto

this book is short, but it lingers. it's about a young woman who loses her last living relative and ends up staying with a classmate and his mother, who is trans. what follows is this soft, subtle story about grief, gender, and the way food holds people together. yoshimoto has a way of making ordinary moments feel weightless and holy. the prose is clean and dreamy, like fog over a city just before sunrise. it’s a book that doesn’t demand anything from you. it just sits quietly with your sadness, offering tea and a place to rest. (japan)

the door by magda szabó

this book completely haunted me. it centers on the relationship between a writer and her fiercely private housekeeper, emerence. at first, it feels like a simple story about two women from different backgrounds learning to understand each other. but it grows into something much stranger and more consuming. their relationship becomes a tangle of love, dependence, betrayal, and worship. szabó writes them with so much restraint that when the emotional weight finally lands, it’s almost unbearable. it’s a novel about trust, power, and the intimacy of knowing someone deeply while never fully understanding them. it asks hard questions and offers no easy answers. (hungary)

the piano teacher by elfriede jelinek

this book made me feel physically uncomfortable. it follows a woman living with her mother, tightly wound and deeply repressed. she teaches piano by day and spends her nights lurking in porn shops and fantasizing about being dominated. then one of her students takes an interest in her, and things get brutal, fast. it’s a book about shame, control, submission, and what happens when a person has been so stripped of agency that even pleasure turns violent. jelinek writes in a way that is almost clinical, with no warmth or apology. the result is a story that feels like it’s pressing its hand against your throat. i couldn’t look away. (austria)

the passion according to g.h. by clarice lispector

this book begins with a woman walking into her maid’s room and seeing a cockroach. that moment becomes the catalyst for a complete collapse of her identity. from there, she spirals into a philosophical and spiritual crisis that stretches far beyond the physical world. this book isn’t interested in plot. it’s about the boundaries of self, the experience of matter, and what it means to exist without language. clarice writes like she’s trying to transcribe a mystical experience while it’s still happening. it’s dense, chaotic, and completely singular. i’ve never read anything like it, and i don’t think anything else even comes close. (brazil)

beware of pity by stefan zweig

this is one of those books that slowly tightens its grip until you can’t breathe. it follows a young austrian soldier in the years before the first world war who becomes entangled with a paralyzed woman out of what he believes is compassion. but what begins as pity curdles into obligation, guilt, and something far more complicated. zweig is so good at writing the kind of psychological drama that doesn’t scream. he’s interested in moral gray zones, in people who mean well and still cause harm, in the quiet, internal tragedies that unfold when someone tries to do the right thing for the wrong reason. this book is full of emotional claustrophobia, and it never lets you off the hook. there’s no real villain here, just two people caught in the unbearable tension between what they owe each other and what they want. (austria)

heaven by mieko kawakami

this novel follows two teenagers who are being horrifically bullied and find a kind of fragile, secret friendship in each other. it’s about what it means to suffer, to endure, and to survive something that never should have happened in the first place. kawakami doesn’t offer simple moral lessons. instead, she explores how cruelty shapes the way we see the world, and how it changes what we’re willing to accept. it’s subtle, uncomfortable, and incredibly brave in the questions it asks about power and complicity. (japan)

breasts and eggs by mieko kawakami

this book moves between two sisters living in tokyo and later zooms in on one of them as she considers becoming a single mother through sperm donation. it’s a novel about women’s bodies, reproductive autonomy, class, and aging. kawakami has this gift for writing about the body in a way that feels intimate and cerebral at the same time. it’s not preachy or dramatic, just deeply honest about the ways womanhood exists at the intersection of physical experience and societal pressure. i loved how this book gave space to doubt, ambivalence, and all the quiet questions no one wants to say out loud. (japan)

the housekeeper and the professor by yōko ogawa

this story is about a housekeeper who goes to work for a brilliant math professor with a condition that causes his memory to reset every 80 minutes. over time, a beautiful connection forms between the professor, the housekeeper, and her young son. it’s not dramatic or plot-heavy, but it’s deeply moving. it’s about routine and care and what it means to find dignity in small, repetitive acts. ogawa writes with such gentleness that even math equations feel tender. this is one of those rare books that makes you feel like the world might still have some quiet magic in it. (japan)

the book of disquiet by fernando pessoa

this book is a series of fragments from a man who lives almost entirely inside his own head. there’s no storyline, no action, no resolution. instead, it’s a collection of thoughts about dreams, boredom, art, time, and the vague ache of existing. it’s not a book you read straight through. it’s a book you return to when you’re feeling disconnected and want something to sit with you in the silence. pessoa’s writing is mournful and meditative, like someone writing letters to a version of themselves that no longer exists. (portugal)

notes from a crocodile by qiu miaojin

set in 1990s taipei, this novel is about a queer university student trying to make sense of her sexuality, her loneliness, and her desire for connection in a world that doesn’t make space for her. it’s written in the form of notebooks, full of obsession, heartbreak, art, and self-destruction. there’s nothing polished or clean about it. it’s messy and raw in a way that feels deeply true. it captures the ache of wanting to be loved without knowing how to be known. (taiwan)

days of abandonment by elena ferrante

this is ferrante at her most feral. the story begins with a woman whose husband suddenly leaves her, and from there, everything unravels. it’s not a story about rebuilding or bouncing back. it’s about descent. ferrante writes the physicality of heartbreak better than anyone. there’s no gloss here, just blood and anger and confusion. it’s a book about rage, motherhood, abandonment, and the unbearable weight of continuing to exist when everything has fallen apart. (italy)

the vegetarian by han kang

after a disturbing dream, a woman decides to stop eating meat. her quiet refusal sets off a chain reaction of horror, obsession, and violence from the people around her. the book is told in three parts, each from a different point of view, none from the woman herself. the result is a story about control, about the violence of forcing someone to conform, and about the terror of a person who simply chooses to disappear. han kang writes with a stillness that makes the most horrific moments feel almost too quiet to bear. (south korea)

white nights by fyodor dostoevsky

a young man wanders the streets of st. petersburg and meets a woman who seems like she might finally pull him out of his solitude. for four nights, they talk, connect, and imagine what a different life could look like. and then it ends. this is one of dostoevsky’s gentler works. it’s about longing, delusion, and the way we project entire worlds onto the people we’re drawn to. it’s tender and dreamy and deeply sad. (russia)

drive your plow over the bones of the dead by olga tokarczuk

this one is part murder mystery, part philosophical treatise, part eco-feminist manifesto. it follows an eccentric older woman in rural poland who begins investigating a series of deaths in her village that seem to align with astrological events. she’s dismissed as crazy, of course, but her voice is unforgettable. the book is strange and smart and full of fury. it’s about animals and justice and how dangerous women become when no one listens to them. (poland)

territory of light by yūko tsushima

this book follows a newly separated mother trying to raise her daughter in a new apartment. the story unfolds over twelve chapters, each one capturing a month in their lives. it’s about loneliness, instability, and the quiet terror of having no one to fall back on. tsushima’s writing is clean and unassuming, but it holds so much. this is a story about light and silence, about the parts of motherhood no one prepares you for, and the slow, painful work of becoming someone new. (japan)

the melancholy of resistance by lászló krasznahorkai

a mysterious circus arrives in a crumbling town, and the sense of doom spreads like fog. what follows is less a plot and more a slow, surreal collapse. this book is heavy and apocalyptic. the sentences are long and winding, like someone trying to explain the end of the world without breathing. it’s about entropy, fear, and the terrifying ease with which people surrender to power when things start to fall apart. unsettling and prophetic in all the ways that matter. (hungary)

okay, that’s all i have for you today.

if you’re not ready to become a paid subscriber and you have the capacity to leave a tip, that would be so appreciated.

i love you.

bye.

(follow ig, tiktok, youtube, pinterest and spotify for more)

I am always so impressed by the art of translation itself - the care translators must take to accurately convey the author's meaning in another language! This is a great list -- I just read "I Who Have Never Known Men" and "Thirst," which were both great translated works!

I am so tremendously happy when someone mentions polish literature 🫶 Olga Tokarczuk is great and I love the attention she gets in mainstream media lately but we have more amazing writers! I implore you to read Bruno Schultz, Wisława Szymborska (also a Nobel laureate), Witold Gombrowicz, Bolesław Prus and many more. It is all yours to explore