hello.

being religious and being haunted by religion...

to be religious is to exist within a system of belief—to move through the world with the certainty of doctrine, ritual, and moral architecture. to be haunted by religion, on the other hand, is to carry the residue of faith long after belief has withered, to find that its language, its ethics, its gravitational pull remain embedded in the psyche even when its metaphysical claims no longer hold.

this is particularly true for those raised in environments where religion was not just a set of beliefs but a totalizing structure of meaning—an architecture that shaped not only morality but memory, language, even the rhythms of daily life. to be born into faith is to be taught, from the moment of consciousness, that existence itself follows a divine order, that suffering is never arbitrary, that love has conditions, and that history—both personal and collective—is moving toward some inevitable judgment. when belief dissolves, these structures remain, not as doctrine but as deep-seated instincts, ways of thinking that resist deconstruction.

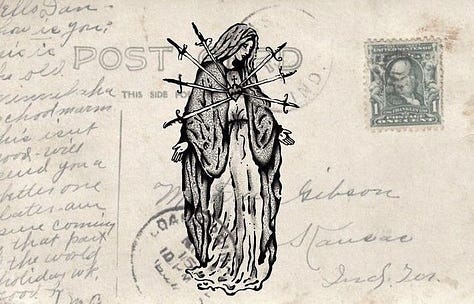

catholicism, with its gothic excesses, its saints and martyrs, its iconography of suffering and redemption, is one of the most persistent hauntings. it is a religion that aestheticizes agony, that elevates the wounds of christ into something beautiful, that teaches its followers from childhood that suffering is not only meaningful but sanctifying. even in disbelief, the weight of its imagery lingers: the scent of incense clinging to the air, the flicker of votive candles, the echo of a prayer whispered instinctively in moments of despair.

evangelicalism, with its ecstatic worship and apocalyptic fervor, breeds another kind of ghost—the ever-present specter of salvation deferred, of sin lurking at the edges of every decision. to grow up evangelical is to internalize the language of spiritual warfare, to see the world as a battleground between good and evil, to believe that one’s soul is always at stake. even after rejecting the theology, former believers often find themselves caught in the binary thinking it engrains, forever searching for the next great revelation, the next moment of transcendence, the next way to be saved.

to leave these faiths is not simply to stop believing. it is to live with the residue of a worldview that refuses to be fully unmade.

raised in a seventh-day adventist household on my mother’s side, then spending the latter half of my weeks with my catholic father and his rotating cast of catholic wives, religion was not just present in my life—it structured every moment of it. mornings in private religious school, weekends split between church and mass, after-school youth groups, family dinners laced with prayer and quiet expectation. it was an all-consuming rhythm, a script i never agreed to but was forced to follow. faith was not just belief; it was surveillance, ritual, duty.

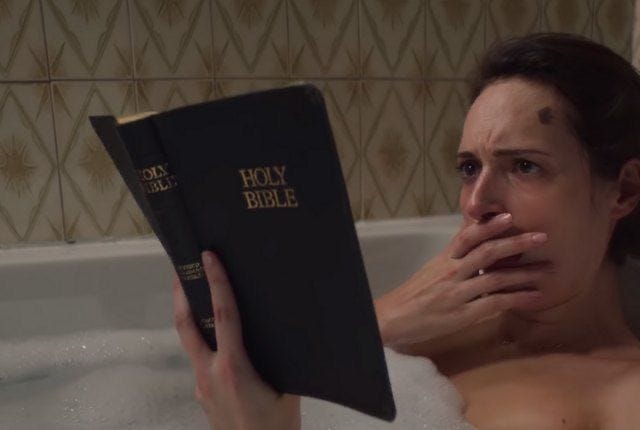

i resented it, every ritual and repetition, every demand for reverence. the weight of sin, the obsession with purity, the quiet fear of damnation—all of it felt like an invisible leash, a force keeping me bound to something i did not choose. i envied those for whom religion was a source of comfort, a gentle certainty rather than a set of rules carved into stone. instead, i memorized prayers i didn’t believe in, recited scripture i longed to disown, bowed my head in moments of silence that felt anything but holy. faith, in theory, was meant to be a source of meaning. in practice, i was a caged bird, longing to free myself from the shackles of religion, yet still whispering prayers under my breath, just in case god was listening.

for many, the process of leaving faith behind is not an act of simple renunciation but a slow and agonizing unspooling of self. it is one thing to reject dogma, another to rewire the subconscious narratives that have dictated one’s relationship to guilt, suffering, love, and even time itself. you may no longer believe in hell, but do you still feel, in some deep and unspoken way, that suffering is redemptive? you may no longer believe in divine judgment, but does the framework of sin and consequence still shape the way you move through the world? do you still flinch at blasphemy? do you still long for transcendence?

god-haunted.

the poetics of suffering

one of the most insidious legacies of religious thought—especially within christian traditions—is the romanticization of suffering. masochism. the idea that pain has meaning, that to suffer is to be purified, that to endure is to be made holy. the martyr, the ascetic, the saint bleeding through their palms—these are the images that linger, even in secular imaginations.

this inheritance finds its way into art, literature, and culture in ways both explicit and subterranean. it is why stories of sacrifice feel noble, why self-destruction in the name of love or art is so often aestheticized, why we still, even now, frame endurance as evidence of moral strength. it is why so many of our greatest literary characters—anna karenina, prince myshkin, the whiskey priest in the power and the glory, even giovanni in giovanni’s room—are not merely people who suffer, but people who are, in some way, sanctified by their suffering. these characters are destroyed, yes, but in their destruction, they achieve a kind of tragic transcendence- a seal of approval from the divine. salvation.

this is a deeply theological structure of feeling. even in its most secular manifestations, it owes something to the long shadow of christianity, to the crucifixion as narrative template, to the idea that suffering is not merely an unfortunate reality but a necessary passage to something higher.

kierkegaard understood this implicitly. in fear and trembling, he writes about the “leap of faith,” the moment when belief defies logic, when one surrenders to the absurdity of divine will. but what is this surrender, if not a kind of self-annihilation? to have faith is to embrace paradox, to accept suffering without reason, to believe that loss, even death, is not merely tragedy but transformation.

this is why faith—even when it is abandoned—leaves behind a residue of longing.

the inescapability of faith’s architecture

even those who reject religious belief often find themselves trapped within its linguistic and moral frameworks. we see it in the way secular culture replicates religious structures: the confessional impulse of social media, the puritanical fervor of ideological purity, the moral absolutism of political discourse. we may no longer believe in divine judgment, but we have never been so eager to proclaim guilt and demand penance.

we see it in art and literature, in the way certain stories still follow the arc of sin, fall, and redemption. we see it in the continued obsession with martyrdom—not only in religious figures but in the way we construct cultural saints, in the way we elevate suffering as proof of authenticity, as though only the broken are truly worthy of reverence. joan of arc, burned alive yet sanctified in death. rainer maria rilke, whose letters and poetry treat suffering as the price of transcendence. pasolini, assassinated on the beach like a modern-day martyr, his art inseparable from his ruin. even virginia woolf, whose genius is often framed as a direct result of her torment, as if her suffering were necessary for her to become eternal. suffering, in this framework, is not merely endured but transfigured—pain as proof of something holy.

and we see it, most of all, in the way the absence of faith still feels like a presence. the ex-believer does not simply become a nonbeliever; they become someone who carries the afterimage of belief, someone who still speaks the language of faith even as they reject its claims. this is why so many former christians find themselves drawn, consciously or not, to narratives of exile and return, of longing and renunciation. it is why the literature of the god-haunted—greene, o’connor, dostoevsky, endō—still resonates, even with those who no longer share their faith.

because to be haunted is to be pursued by something unseen. and what is god, if not precisely that?

the ache of the abandoned altar

perhaps this is why so many people who leave faith behind never fully escape its influence. it is not merely a set of beliefs that is abandoned, but an entire cosmology, a way of understanding love, suffering, and time itself. religion does not just offer answers; it provides a framework, a narrative structure in which every experience, every joy, every loss has meaning. when that structure collapses, what is left is not freedom, but disorientation—a sudden, vertiginous awareness of how much belief shaped even the most mundane aspects of life.

and what replaces it? some find meaning in philosophy, attempting to rebuild a coherent worldview from reason and existential inquiry. others turn to art, literature, or music, seeking transcendence in the secular echoes of the divine. politics, activism, intellectual rigor—these, too, become sites of devotion, systems of faith built on different foundations. but the absence of religion is rarely a clean slate; it lingers in the metaphors we use, in the moral intuitions we cannot shake, in the instinct to search for purpose even in a world we now believe to be indifferent.

some people, unable or unwilling to replace what they have lost, simply learn to live with the absence, with the empty space where belief once was. they carry it like a phantom limb, something once vital that still aches despite its disappearance. they may no longer kneel in prayer, but they still move through the world as though waiting for an answer, a revelation, a moment of clarity that may never come. and in this way, faith—even in its absence—continues to shape them, not as a god they worship, but as a ghost that refuses to be exorcised.

but an absence is still a presence.

and so we remain god-haunted, even in disbelief. we still dream in the language of faith, still structure our stories in the shape of sacrifice, still long, in some deep and wordless way, for something holy.

maybe it isn’t god we miss.

maybe it’s the feeling of believing in something vast enough to hold us.

books and film recommendations rooted in faith, doubt, and the inescapability of religion…

books:

fear and trembling by søren kierkegaard – the ultimate text on faith as paradox, sacrifice as devotion, and the terrifying absurdity of belief.

lapvona by ottessa moshfegh – a dark, medieval fever dream of a novel, where faith is inseparable from power, violence, and the delusions people create to endure suffering. moshfegh dissects the ways religion can be manipulated, showing how belief is often less about salvation and more about control, survival, and self-deception.

an oresteia by anne carson – a fierce, poetic retelling of the orestes myth, weaving together aeschylus, sophocles, and euripides to explore fate, divine justice, and the inescapability of inherited guilt. carson strips these tragedies down to their rawest form, where suffering is inevitable, the gods are merciless, and faith feels less like salvation and more like a curse.

eros the bittersweet by anne carson – a philosophical meditation on desire, absence, and the way longing itself creates meaning. carson explores eros as both pleasure and pain, connecting it to the paradox of faith—wanting something just beyond reach, existing in the space between presence and loss. love, like belief, is an ache that refuses to be resolved.

the passion according to g.h. by clarice lispector – a novel about religious crisis, self-annihilation, and transformation. g.h.’s encounter with a cockroach triggers a complete breakdown of identity, blurring the lines between faith, suffering, and ecstasy. it reads like an act of mystical surrender, a decreation of the self in the face of something vast and indifferent. perfect for your themes of martyrdom and the paradox of belief.

the piano teacher by elfriede jelinek – repression, power, and the disturbing undercurrents of religious morality. suffocating and brutal.

demons by fyodor dostoevsky – a chaotic, fevered novel about ideology, nihilism, and the spiritual void left when faith collapses. dostoevsky dissects the consequences of rejecting god—not just personally, but on a societal level—showing how a world without belief spirals into destruction. filled with religious symbolism, political upheaval, and existential dread, demons feels like an exorcism in novel form, where the ghosts of faith linger even in those who claim to have abandoned it.

beloved by toni morrison – suffering as inheritance, love as both salvation and destruction. a ghost story in every sense.

silence by shūsaku endō – a brutal, beautiful novel about jesuit priests in japan, persecution, and the agony of faith in the face of divine silence.

confessions by saint augustine – an intellectual and deeply emotional account of sin, redemption, and the restlessness of the soul.

brideshead revisited by evelyn waugh – catholic guilt and doomed love, drenched in nostalgia and the ache of lost innocence.

the flowers of evil by charles baudelaire – decadence, sin, and the beauty of ruin. one of the great poetic testaments to being god-haunted.

the idiot by fyodor dostoevsky – a christ-like figure wandering through a world that cannot hold him, exploring innocence, suffering, and spiritual transcendence.

the brothers karamazov by fyodor dostoevsky – the definitive novel of faith, doubt, suffering, and moral reckoning. ivan’s “grand inquisitor” chapter alone is worth the read.

house of incest by anais nin – surreal, poetic, and deeply symbolic. reads like a religious vision turned inside out.

the exorcist by william peter blatty – possession as metaphor for faith, doubt, and the body as a battleground for the divine.

morte d’urban by j.f. powers – a satirical yet deeply melancholic novel about a priest grappling with cynicism and the slow decay of faith.

the seven storey mountain by thomas merton – a real-life confessions, detailing merton’s journey from a hedonistic young man to a trappist monk.

carmilla by sheridan le fanu – queerness, catholic guilt, and the seductive power of the forbidden.

films:

brideshead revisited (1981) – one of the most visually lush depictions of catholic guilt and doomed love.

the exorcist (1973) – possession as crisis of faith, the priest’s battle as much internal as external.

black narcissus (1947) – nuns battling both the divine and their own desires. lush, hypnotic, and unsettling.

the double life of véronique (1991) – two women, unknowingly linked across space and time. dreamlike and melancholic.

calvary (2014) – an irish priest is told he will be murdered in one week. darkly funny, devastating, and soaked in catholic guilt.

orpheus (1950) – jean cocteau’s take on the orpheus myth, filled with surreal, poetic longing.

the piano (1993) – an eerie, gothic love story set against a harsh, elemental landscape. sensual and unsettling.

possession (1981) – the most unhinged breakup movie ever. body horror, religious symbolism, and absolute madness.

in the mood for love (2000) – lingering glances, unspoken desires, aching nostalgia. a film that feels like memory.

the handmaiden (2016) – betrayal, love, and power wrapped in a stunning, gothic thriller.

phantom thread (2017) – control, obsession, love as a battle of wills. intoxicatingly beautiful.

l’atalante (1934) – one of the most romantic films ever made, but in the strangest, most ethereal way.

okay, that’s all for today.

if you’re not ready to become a paid subscriber and you have the capacity to leave a tip, that would be so appreciated.

i love you.

bye.

(follow ig, tiktok, youtube, pinterest and spotify for more)

I wonder if you have come across the the English mystic, Julian of Norwich. Her writings - Revelations of Divine Love are so interesting. So dangerous for anyone writing about such things in the 1400s, but for a woman then it was even more so.

Desperately hungry for intellectuals to reclaim the “spiritual/mystical, not religious” identity from people who wouldn’t be able to comprehend this essay. It is a profound foundational ideological structure, not just a tagline for those who shop for crystals.